A New View in Japan

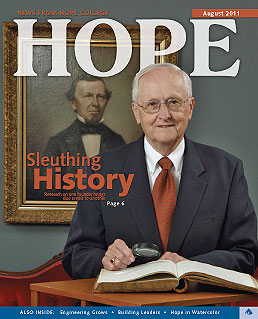

Wei Yu Wayne Tan, Ph.D. | Assistant Professor of History

It’s an unusual question for a historian: What is it like for a blind person to live in a world dominated by sighted people? But this inquiry, with a particular focus on Japan, is at the heart of Dr. Wayne Tan’s research.

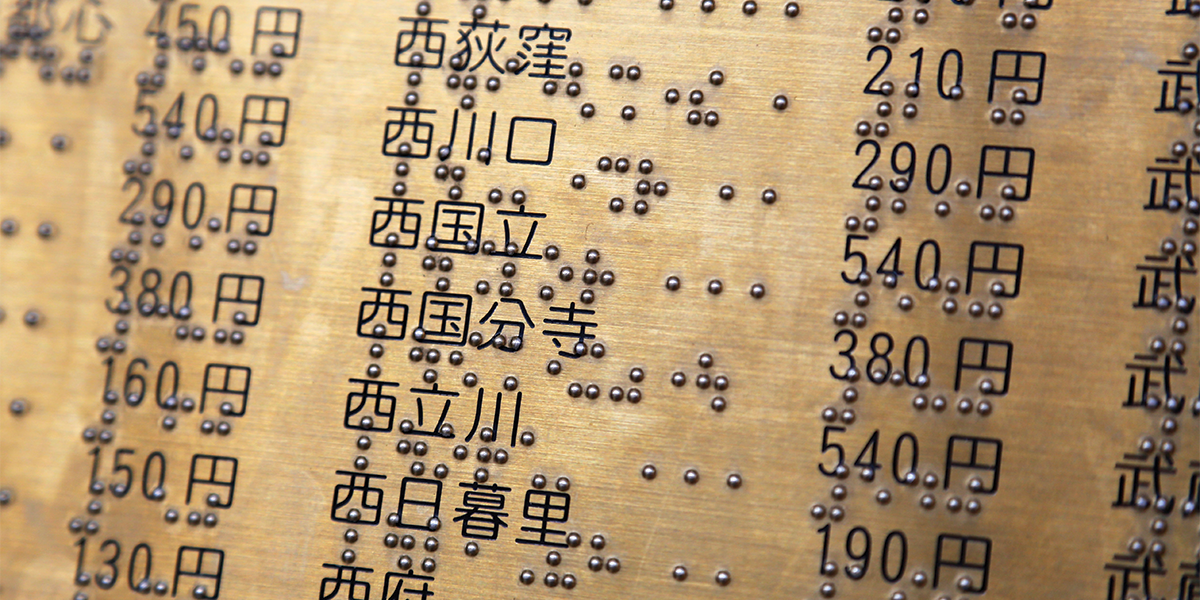

Today, Japan is considered one of the most blind-friendly nations in the world, providing aids like braille signs and audio signals in public spaces. To get to this point, Japan experienced many social and cultural shifts — and Tan has been studying those shifts since his days at Harvard University.

In his doctoral dissertation at Harvard, Tan explored how blind people were viewed in Japan from the 17th century through the mid-19th century. Now, he is expanding his study as he writes a book, tentatively titled Blindness as Disability in Japan, which extends the timeline into the modern era. Conducting research for the book, Tan pored over medical and scientific reports about disability, as well as personal memoirs, education policies, village registers, records of temples and shrines, and the digital collections of the National Diet Library, Japan’s national library.

Tan points out that in early Japanese society there were groups of blind traveling musicians who played a stringed instrument known as the biwa.

The genres these musicians performed were of a literary, lyrical, and, sometimes, religious nature. “Blind people were, in fact, employed in a number of specialized professions and belonged to institutions unlike any seen in Western countries,” Tan says.

But with the emergence of the modern Japanese state in the late 19th century, blind communities came under new forms of state control and were forced onto the margins of society. In the 20th century, Western influence changed again how those dealing with blindness were viewed.

“The dominant narrative tells us that Japan caught up with the rest of the world by importing and adapting ideas from Western nations, and would go further to suggest that the levels of provision for blind and disabled populations were the outcome of modernity,” Tan says. “Yet, what I hope to highlight through my case studies is that disability did not go away, but reemerged in more recognizable terms, actually, because of the Western models that guided Japan’s modernizing process.”

“Disability,” says Tan, “is a culturally subjective experience.”

One thought on “A New View in Japan”

Comments are closed.